|

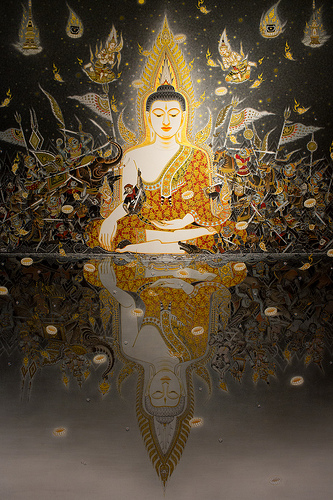

| Golden plump Shakyamuni Buddha, Wat Muang, Thailand (Krunja Photography/flickr.com) |

.

The Noble Eightfold Path offers a comprehensive practical guide to the development of those wholesome qualities and skills in the heart/mind that must be cultivated in order to bring practitioners to the final goal, the supreme freedom and joy of nirvana.

The Noble Eightfold Path offers a comprehensive practical guide to the development of those wholesome qualities and skills in the heart/mind that must be cultivated in order to bring practitioners to the final goal, the supreme freedom and joy of nirvana.

The eight qualities to be developed are: right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration.

In practice, the Buddha taught the Noble Eightfold Path to skeptics and admirers according to a "gradual" system of training, beginning with the development of sila (virtue: right speech, right action, and right livelihood, which are summarized in practical form by the Five Precepts).

- I undertake to abstain from taking life.

- I undertake to abstain from taking what is not given.

- I undertake to abstain from taking sexual liberties.

- I undertake to abstain from taking the truth lightly.

- I undertake to abstain from taking intoxicants that occasion carelessness [the breaking of these profitable undertakings due to intoxicated negligence].

This is followed by the development of samadhi (collectedness, concentration, or mental-cultivation: right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration), culminating in the development of panna (wisdom, knowledge, insight: right view, right intention).

The practice of generosity (dana) serves as a support at every step along the path to enlightenment, as it helps foster the development of a compassionate mind/heart and counters the heart's habitual tendencies towards craving.

Progress along the path does not follow a simple or linear trajectory. Rather, development of each aspect of the Noble Eightfold Path encourages the refinement and strengthening of the others, leading the practitioner ever forward in an upward spiral of spiritual maturity that culminates in enlightenment.

Seen from another point of view, the long journey on the path to nirvana begins in earnest with the first tentative stirrings of right view, the first flickerings of wisdom by which one recognizes both the validity of the first Noble Truth and the inevitability and hope of the law of karma, the universal law of actions and results.

Once one begins to see that harmful actions (karma) inevitably bring about painful results, and wholesome actions ultimately bring about pleasant results, the desire naturally grows to live a skillful, morally upright life, to take seriously the practice of virtue.

The confidence built from this preliminary understanding inclines a practitioner/follower to put one's trust more deeply in the Dharma, the path-of-practice. The follower becomes a "Buddhist" upon expressing an inner resolve to "go for guidance" to the Triple Gem:

- the Buddha (both the historical Teacher and one's own innate potential for enlightenment),

- the Dharma (both the teachings of the historical Buddha and the ultimate Truth towards which they point), and

- the Sangha (both the monastic community that has protected the teachings and put them into practice since the Buddha's day, and the true Sangha, the "noble ones," all lay-practitioners and monastics who have achieved at least the first stage of enlightenment called stream entry).

With one's feet firmly planted on the ground by going for guidance to enlightened/accomplished beings, and with the help of a noble friend (kalyana-mitta) to help show the way, one can set out on the Path, confident that one is indeed following in the footsteps left by the Buddha himself.

|

| Remember what the Buddha taught in the Kalama Sutra: Think for yourself. |

Buddhism is sometimes criticized as a "pessimistic" or "negative" philosophy. After all (the argument goes), life is not all disappointment and misery, woe and suffering: It offers many kinds of joy and happiness, bliss and rapture. Why then this pessimistic Buddhist obsession with "unsatisfactoriness" and suffering (dukkha)?

The reason the Buddha bases the Teachings on a frank assessment of our plight as humans and devas is that there is disappointment and unsatisfactoriness, woe and suffering in life. No one can argue this; it's a fact. If the Buddha's teachings were to stop there, the Dharma might indeed regard Buddhism as pessimistic and life as utterly hopeless.

But like a doctor prescribing a remedy for an illness (dukkha), the Buddha offers hope (the third Noble Truth) and a cure (the fourth Noble Truth)! [Why did he place the problem at the beginning? That's where a skillful doctor usually begins: the problem, the cause, the solution, the things to do.]

It is important to keep in mind that the Buddha never denies that life -- even an "unenlightened" life -- holds the potential and possibility of many great kinds of happiness. He also recognized that the kinds of happiness to which most of us are accustomed cannot, by their very nature, give us lasting satisfaction.

The reason the Buddha bases the Teachings on a frank assessment of our plight as humans and devas is that there is disappointment and unsatisfactoriness, woe and suffering in life. No one can argue this; it's a fact. If the Buddha's teachings were to stop there, the Dharma might indeed regard Buddhism as pessimistic and life as utterly hopeless.

But like a doctor prescribing a remedy for an illness (dukkha), the Buddha offers hope (the third Noble Truth) and a cure (the fourth Noble Truth)! [Why did he place the problem at the beginning? That's where a skillful doctor usually begins: the problem, the cause, the solution, the things to do.]

It is important to keep in mind that the Buddha never denies that life -- even an "unenlightened" life -- holds the potential and possibility of many great kinds of happiness. He also recognized that the kinds of happiness to which most of us are accustomed cannot, by their very nature, give us lasting satisfaction.

If we are genuinely interested in our own and others' welfare, we must sometimes be willing to give up one kind of happiness for the sake of gaining something much better.

|

| The Buddha (VIctoria & Albert Museum) |

Each level of happiness has its rewards, but each also has its drawbacks -- the most conspicuous of which is that it cannot, by its very nature, endure.

The highest happiness of all, the one to which all of the Buddha's Teachings ultimately point, is the lasting happiness and peace of the transcendent, the Deathless, the Unconditioned, nirvana.

So the Buddha's Teachings are concerned solely with guiding people toward the highest and most expansive happiness possible. There is nothing pessimistic about that. In the words of one teacher, "Buddhism is the serious pursuit of happiness."

The Buddha claimed that the awakening he rediscovered is accessible to anyone willing to put forth the effort and commitment required to pursue the Noble Eightfold Path to its ultimate aim. It is up to each of us individually to put that claim to the test.

Theravada comes West

|

| Burma, now Myanmar, is perhaps the most Theravada country (Alex Eidlin/flickr). |

Until the late 19th century, the teachings of Theravada Buddhism were little known outside of South and Southeast Asia, where they had flourished for two and a half millennia. In the last century, however, the West has begun to take notice of Theravada's unique spiritual legacy and teachings of enlightenment.

In recent decades, this interest has swelled; the monastic Sangha from various Theravada cultures has established dozens of monasteries across Europe and North America. In addition, a growing number of Western lay meditation centers, operating independently of the Sangha, currently strain to meet the demands of lay people -- Buddhist and otherwise -- seeking to learn selected aspects of the Buddha's Teachings, the "Doctrine of the Elders."

The turn of the 21st century presents opportunities and dangers for Theravada in the West: Will the Buddha's classical Teachings, which are called the Buddha-Dharma, be patiently studied and practiced so that they establish deep roots in Western soil, for the benefit of many generations to come?

Will the current popular climate of "openness" and cross-fertilization between the many different schools of Buddhism lead to the emergence of a strong new form of Buddhism unique to the West, or will it simply lead to the dilution and confusion of all of these priceless teachings? These are open questions, and only time will tell.

|

| Pali language canonical and exogenous texts |

Invitation to explore

|

| The Buddha was enlightened. We can be, too, but it depends on our own practicing. |

A link exists to Web pages (Access to Insight) along with an invitation to explore the historical Buddha's Teachings from the Theravada perspective. Where can one begin? See the article "Befriending the Sutras: Some Suggestions for Reading the Pali Discourses."

Keep in mind that these Teachings are not meant to be studied, analyzed, critiqued, and wondered about. They are meant to be investigated and put into PRACTICE, put to the test in our heart.

They challenge us to awaken within ourselves the same liberating truths the Buddha rediscovered long ago on a full-moon night in the month of May, in a forest grove near Gaya, India.

No comments:

Post a Comment