Dhr. Seven, Amber Larson, Crystal Quintero (eds.), Wisdom Quarterly; Ven. Nyanatiloka Maha Thera, Manual of Buddhist Terms and Doctrines (viññāna)

|

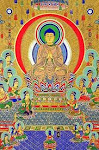

| Buddhas of the past, sacred Dambulla cave, Sri Lanka (inquiringmind.com) |

.

|

| How are living beings conscious? (WHP) |

Viewed as one of the Five Aggregates [trillions of discrete phenomena lumped into five groups or categories], it is inseparably linked with the three other mental aggregates (feeling, perception, and formations) and furnishes the bare cognition of the object, while the other three contribute more specific functions.

|

| Conscious awareness (dhammawheel.com) |

Its moral and karmic character, and its greater or lesser degree of intensity and clarity, are chiefly determined by the mental formations associated with it (particularly the most salient formation, "volition" or cetana, which determines if a karmic act is beneficial, unwholesome, or neutral).

Just like the other aggregates or "groups of existence," consciousness is not so much a thing as a flux (sotā, a "stream of consciousness") and does not constitute an abiding mind-substance.

|

| Free your mind. Rest will follow. |

The Three Marks or Characteristics of Existence (the impermanent, unsatisfactory/disappointing/woeful, and impersonal nature of all conditioned phenomena) are frequently applied to consciousness in the texts (e.g., in the Anattalakkhana Sutra, S.XXII, 59).

|

| The physical base of the "mind" is the heart (K) |

The Buddha often stresses that "apart from conditions, there is no arising of consciousness" (MN 38). And all of these statements about its nature hold good for the entire range of consciousness -- be it "past, future, or presently arisen, gross or subtle, in oneself or another, that is, internal or external, inferior or lofty, far or near" (S. XXII, 59).

Six consciousnesses

|

| The seven main chakras,energy centers, along the spine (Manifesto-Meditations) |

According to the six senses it divides into six kinds: eye- (or visual), ear- (auditory), nose- (olfactory), tongue- (gustatory), body- (tangible), mind- (mental, intuitive, memory, psychic) consciousness.

About the dependent origination or arising of these six kinds of consciousness, the Path of Purification (Vis.M. XV, 39) says:

- "Conditioned through the [sense base or sensitive portion within the] eye, the visible object, light, and attention, eye-consciousness arises.

- Conditioned through the ear, the audible object, the ear-passage, and attention, ear-consciousness arises.

- Conditioned, through the nose, the olfactive object, air, and attention, nose-consciousness arises.

- Conditioned through the tongue, the gustative object, humidity, and attention, tongue-consciousness arises.

- Conditioned through the body, bodily impression, the earth-element [the solid quality of materiality or rupa], and attention, body-consciousness arises.

- Conditioned through the subconscious [or default, underlying] mind (bhavanga-mano [manas, mind]), the mind-object, and attention, mind-consciousness arises."

The Abhidharma literature distinguishes 89 classes of consciousness as being either karmically wholesome (skillful), unwholesome (unskillful), or neutral, and belonging either to the Sensual Sphere, the Fine-Material Sphere, or the Immaterial Sphere, or to supermundane consciousness. See Table I for the detailed classification.