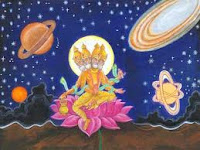

Is "God" (Maha Brahma) the ruler and responsible party for all that happens throughout "creation" in the infinitely expanding sensual universe, before it contracts again and a new Maha Brahma assumes the top seat? Impersonal karma or "GOD" (Brahman) may be all things everywhere, but Maha Brahma is not the personal creator/judge.

Is "God" (Maha Brahma) the ruler and responsible party for all that happens throughout "creation" in the infinitely expanding sensual universe, before it contracts again and a new Maha Brahma assumes the top seat? Impersonal karma or "GOD" (Brahman) may be all things everywhere, but Maha Brahma is not the personal creator/judge. The title Mahābrahmā appears in numerous discourses. It is applied to an extraterrestrial, possibly transdimensional, being(s) of the third superhuman world of the Sensual Sphere (rūpadhātu).

The title Mahābrahmā appears in numerous discourses. It is applied to an extraterrestrial, possibly transdimensional, being(s) of the third superhuman world of the Sensual Sphere (rūpadhātu).There are numerous, possibly innumerable, Great Brahmas because there are innumerable world-systems (solar systems, galaxies, or universes composed of 31 general planes of existence) scattered throughout the universe/multiverse.

The word brahma (supreme) is frequently met with as a reference to exalted devas ("shining ones") and the beings beyond the Sense Sphere. It is not an exact term but one used for many kinds of higher order entities/deities. This brahma is called "Great Brahma" because it sits atop the Sense Sphere, at the lowest rung of the Fine-Material Sphere and far below planes it is not even aware of known as the Immaterial Sphere.

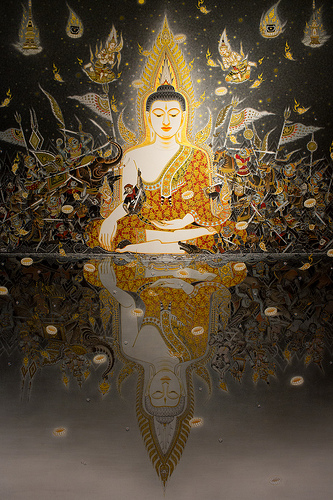

There is no sexual dimorphism beyond the Sensual Sphere, so there is no chance that God is male or female. It is either, it is neither, it is both. Brahmas and devas can manifest as they wish without themselves being locked into one gendered form or another. So it is very misleading to refer to God as "He." It may act like a father, protect and create like a mother, or simply be eminent.

There is no sexual dimorphism beyond the Sensual Sphere, so there is no chance that God is male or female. It is either, it is neither, it is both. Brahmas and devas can manifest as they wish without themselves being locked into one gendered form or another. So it is very misleading to refer to God as "He." It may act like a father, protect and create like a mother, or simply be eminent.

A Mahābrahmā's titles are: "Brahmā, Great Brahmā, the Conqueror, the Unconquered, the All-Seeing, All-Powerful, the Lord, the Maker and Creator, the Ruler, Appointer and Orderer, Father of All That Have Been and Shall Be."

So this Vedic, pre-Buddhist idea may well refer to the God(s) of the Bible, the monotheistical figure of lore, a great space being lauded by many archangelic devas and gandharvas (messengers of the devas) who have been visiting Earth for millenia.

According to the "Net of All-Embracing Views" (Brahmajāla Sutta, DN 1), a Mahābrahmā is a being from the Ābhāsvara worlds who falls into a lower world through exhaustion of its merits and is reborn alone in the Brahma-world.

Forgetting its former existence (because lifespans are extraordinarily long and measures in ages), it imagines itself to have come into existence without a cause. It therefore sees itself as a "causeless cause," a first cause, a prime mover.

Beings who have been reborn from that world into the human world and are able to recover a memory of it believe that being to be the "creator of the world." Indeed, such beings may terraform planets, conjure up galaxies or stars, but in no way are they in fact "creating" something out of nothing. There already exists materials (basic elements or building blocks), laws (of physics), karma, entities, and more.

Beings who have been reborn from that world into the human world and are able to recover a memory of it believe that being to be the "creator of the world." Indeed, such beings may terraform planets, conjure up galaxies or stars, but in no way are they in fact "creating" something out of nothing. There already exists materials (basic elements or building blocks), laws (of physics), karma, entities, and more.In the Kevaddha Sutra (DN 11), a Mahābrahmā is unable to answer a philosophical question put forward by a monk. But the Great Brahma conceals this fact from the devas of the retinue so as not to lose face in front of them. Addressing that monk privately, the monk is told to ask the Buddha this perplexing question if he wants an answer.

Non-Buddhist views refuted

The old Upanishads largely consider Brahman, regarded as masculine gender (Brahmā in the nominative case), to be a personal god, whereas Brahman in the neuter gender (Brahma in the nominative case, GOD or "Brahman") to be the impersonal world principle.

However, they do not strictly distinguish between the two.

The old Upanishads ascribe the following characteristics to Brahmā: first, he has light and luster as his marks; second, he is invisible; third, he is unknowable, and it is impossible to know his nature; fourth, he is omniscient. But the old Upanishads ascribe these characteristics to Brahman as well (Hajime Nakamura, A History of Early Vedānta Philosophy: Part One. Reprint by Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1990, p. 136).

In the Buddhist texts, there are many brahmās. There they form a class of superhuman beings. Rebirth into the realm of brahmās is possible through the pursuit of virtue (sila) and concentration (samadhi), which are not exclusively Buddhist practices.

In the early texts, the Buddha gives arguments to refute the existence of a creator (David Kalupahana, Causality: The Central Philosophy of Buddhism. The University Press of Hawaii, 1975, pp. 20-22).

In the Pāli language scriptures, the neuter Brahman does not appear. (The standard word brahma is used in compound words to mean "supreme," "best," or "highest" (Steven Collins, Aggañña sutta. Sahitya Akademi, 200, p. 58; Peter Harvey, The Selfless Mind. Curzon Press, 1995, p. 234).

But ideas are mentioned as held by various brahmins, the intellectual priestly caste of ancientIndia, in connection with Brahmā that match exactly the concept of Brahman in the Upanishads.

Brahmins who appear in the Tevijja Sutra (DN) regard "union with Brahmā" as liberation (moksha) and earnestly seek it. In that text, brahmins of the time are reported to assert:

"Truly every brahmin versed in the three Vedas has said thus: 'We shall expound the path for the sake of union with that which we do not know and do not see. This is the correct path. This path is the truth that leads to liberation. If one practices it, he shall be able to enter into association with Brahmā."

"Truly every brahmin versed in the three Vedas has said thus: 'We shall expound the path for the sake of union with that which we do not know and do not see. This is the correct path. This path is the truth that leads to liberation. If one practices it, he shall be able to enter into association with Brahmā."

The early Upanishads frequently expound "association with Brahmā" and "that which we do not know and do not see" matches exactly with the early Upanishadic Brahman (Nakamura, 1990, p. 137).

In the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, the earliest Upanishad, the Absolute, which came to be referred to as Brahman, is referred to as "the imperishable" (Karel Werner, The Yogi and the Mystic: Studies in Indian and Comparative Mysticism. Routledge, 1994, p. 24).

The Pāli scriptures present a "pernicious view" that is set up as an absolute principle corresponding to Brahman: "O monastics! At that time Baka Brahmā produced the following pernicious view: 'It is permanent. It is eternal. It is always existent. It is independent existence. It has the dharma of non-perishing. Truly it is not born, does not become old, does not die, does not disappear, and is not reborn. Furthermore, no liberation superior to it exists elsewhere."

The principle expounded here corresponds to the concept of Brahman laid out in the Upanishads. According to this text the Buddha criticized this notion: "Truly Baka Brahmā is covered with unwisdom" (Nakamura, 1990, pp. 137-138. "It has the dharma of non-perishing" is Nakamura's translation of "acavanadhammam").

The historical Buddha confined himself to what is empirically given (Kalupahana, 1975, p. 185; Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, p. 202; A.K. Warder, A Course in Indian Philosophy. 2nd edition, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1998, p. 81).

This "empiricism" is not limited to scientific objectivism but based broadly on both ordinary sense experience and extrasensory perception enabled by high degrees of mental concentration (David J. Kalupahana, Buddhist philosophy: A Historical Analysis. Published by University of Hawaii Press, 1977, pp. 23-24).

Moreover, meditators who develop the eight attainments (the four material and four immaterial meditative absorptions) can verify what the Buddha taught regarding the 31 Planes of Existence and the countless inhabitants therein, including Maha Brahma.

No comments:

Post a Comment