Wisdom Quarterly; Susan Murcott The First Buddhist Women

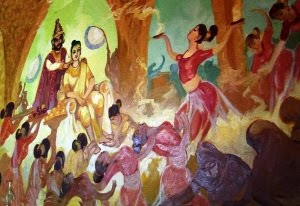

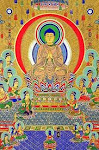

Siddhartha in the palace surrounded by beautiful women (chandawimala.blogspot.com)

Siddhartha in the palace surrounded by beautiful women (chandawimala.blogspot.com)

Siddhartha in the palace surrounded by beautiful women (chandawimala.blogspot.com)

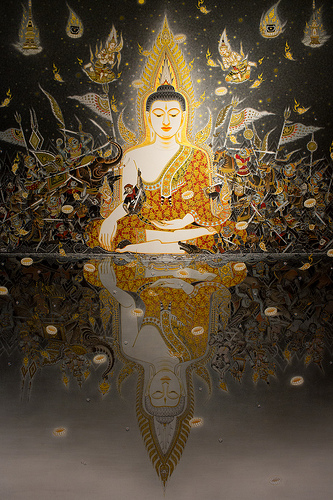

Siddhartha in the palace surrounded by beautiful women (chandawimala.blogspot.com)The greatest thing about Siddhartha, who awakened to become "the Buddha," was that he was human.

A buddha is more than superhuman; he is unsurpassed among all kinds of beings. This is why the historical Buddha is referred to as a "teacher of gods and men." Here "gods" refers to light beings called devas and brahmas, and "men" of course refers to human beings.

Siddhartha sets an example of what we are capable of, rather than a celestial savior who comes down and bosses people around.

Siddhartha sets an example of what we are capable of, rather than a celestial savior who comes down and bosses people around.

This idea is so compelling and beautiful that at least one other world religion has borrowed it to play both sides of the fence by claiming a divine savior who is nevertheless human, a humble blue collar worker who is somehow really a king, fully human but a complete virgin by the time he dies at 33. (And, oh, wait, he didn't die but came back to life after not being dead).

We all have divine-potential. The Buddha points it out. (That other teacher may also have gotten in trouble for the heresy of pointing that out):

We can become devas ("angels," in a sense, by karma), brahmas (divine rulers by mastery of the jhanas), humans again (by the precepts), or enlightened beings (by concentration and insight meditation in this very life). We can even become buddhas, supremely enlightened teachers (by developing the Ten Perfections) if we so wish.

Good Times in the Palace

Before becoming a wanderer, a yogi, a recluse, an ascetic, a meditator, Siddhartha lived in luxury. This luxury included sensual delights of all kinds. He was able to speak of their pitfalls precisely because he had known them directly. He had much more pleasure and wisdom in his ancient life than we in our modern one.

Before becoming a wanderer, a yogi, a recluse, an ascetic, a meditator, Siddhartha lived in luxury. This luxury included sensual delights of all kinds. He was able to speak of their pitfalls precisely because he had known them directly. He had much more pleasure and wisdom in his ancient life than we in our modern one.

He did not experience to find out, or he would have never found out. It was by renouncing it that he found it. So long as one remains trapped in craving for sense pleasures, one never knows the full extent of their danger or unsatisfactoriness.

So it it with the utmost appreciation and devotion that we discuss Siddhartha's harem, rejoicing that he was first human before showing what humans are capable of. For those who deify him and regard him as a God, a messenger of the gods (gandharva deva), a giant (asura), or a superhuman entity (brahma, naga, or yakkha), rest assured the Buddha did not have a harem.

"My darling, will you... hold on a minute!" (uberhumor.com)

"My darling, will you... hold on a minute!" (uberhumor.com)

A buddha is more than superhuman; he is unsurpassed among all kinds of beings. This is why the historical Buddha is referred to as a "teacher of gods and men." Here "gods" refers to light beings called devas and brahmas, and "men" of course refers to human beings.

Siddhartha sets an example of what we are capable of, rather than a celestial savior who comes down and bosses people around.

Siddhartha sets an example of what we are capable of, rather than a celestial savior who comes down and bosses people around.This idea is so compelling and beautiful that at least one other world religion has borrowed it to play both sides of the fence by claiming a divine savior who is nevertheless human, a humble blue collar worker who is somehow really a king, fully human but a complete virgin by the time he dies at 33. (And, oh, wait, he didn't die but came back to life after not being dead).

We all have divine-potential. The Buddha points it out. (That other teacher may also have gotten in trouble for the heresy of pointing that out):

We can become devas ("angels," in a sense, by karma), brahmas (divine rulers by mastery of the jhanas), humans again (by the precepts), or enlightened beings (by concentration and insight meditation in this very life). We can even become buddhas, supremely enlightened teachers (by developing the Ten Perfections) if we so wish.

Good Times in the Palace

Before becoming a wanderer, a yogi, a recluse, an ascetic, a meditator, Siddhartha lived in luxury. This luxury included sensual delights of all kinds. He was able to speak of their pitfalls precisely because he had known them directly. He had much more pleasure and wisdom in his ancient life than we in our modern one.

Before becoming a wanderer, a yogi, a recluse, an ascetic, a meditator, Siddhartha lived in luxury. This luxury included sensual delights of all kinds. He was able to speak of their pitfalls precisely because he had known them directly. He had much more pleasure and wisdom in his ancient life than we in our modern one.He did not experience to find out, or he would have never found out. It was by renouncing it that he found it. So long as one remains trapped in craving for sense pleasures, one never knows the full extent of their danger or unsatisfactoriness.

So it it with the utmost appreciation and devotion that we discuss Siddhartha's harem, rejoicing that he was first human before showing what humans are capable of. For those who deify him and regard him as a God, a messenger of the gods (gandharva deva), a giant (asura), or a superhuman entity (brahma, naga, or yakkha), rest assured the Buddha did not have a harem.

"My darling, will you... hold on a minute!" (uberhumor.com)

"My darling, will you... hold on a minute!" (uberhumor.com)Is Marriage the Only Sexual Relationship?

When was sex ever limited to "marriage"?

When was sex ever limited to "marriage"?Nevertheless, the idea that one goes exclusively with the other is an idea promoted by many religions. Christian fundamentalists will not allow any discussion of premarital, extramarital, or polygamous arrangements even as codified in their own sacred texts. But hypocrisy is never helpful to anyone.

Siddhartha Gautama was married off, as was the custom among warrior (kshatriya) caste nobles, at a young age. Presumably to keep the royal bloodline pure, he was paired with his cousin Yasodhara, both at the age of 16. (Familial lines and what is considered acceptable between them is far from universal, so their marriage was not considered unusual).

Theravada tradition puts forward the idea that Yasodhara had vowed to help the Bodhisatta reach buddhahood many lives ago and had therefore been reborn as his wife countless times. But as a royal prince Siddhartha was surrounded by beautiful women -- guarding his winter palace and providing constant entertainment and distractions from the world outside.

Author Susan Murcott refers to these guards, musicians, dancers, cooks, and servants as Siddhartha's "harem."

King Suddhodana, his father, encouraging Prince Siddhartha to take delight in sensual pleasures of the royal life (theosophywatch.com).

King Suddhodana, his father, encouraging Prince Siddhartha to take delight in sensual pleasures of the royal life (theosophywatch.com).Indeed, it seems difficult to believe that a young prince living in extreme luxury and indulging his senses would not have had a harem. Members of the harem would have been single.

- "Sexual misconduct" is NOT defined, technically as preserved in ancient sexist texts, as sex by a married male for what many mistranslators commonly call "adultery." It is defined as sex with a married (or otherwise dependent) female regardless of one's own marital status.

To quote Murcott, "Though it is seldom mentioned, Gautama, besides leaving a wife and child [temporarily until he reached his goal and returned to share it with them], left a harem of [Sakyan] women. Twelve of these women resurface as one who join [his adoptive mother] Pajapati in founding the community of nuns."

To quote Murcott, "Though it is seldom mentioned, Gautama, besides leaving a wife and child [temporarily until he reached his goal and returned to share it with them], left a harem of [Sakyan] women. Twelve of these women resurface as one who join [his adoptive mother] Pajapati in founding the community of nuns."This may shock or scandalize some in the West. But it is only because of assumptions about sex and how "bad" it is. Sexual misconduct is bad, not sex itself. Sensual craving binds one to rebirth, unsatisfactoriness, leads one down a dangerous road, but the reason we crave is due to ignorance -- not seeing things as they really are.

One can be quite contented to be celibate when one sees sex, the body, and the hidden dangers of addiction to sensuality. Otherwise, we crave sex. It is the banner form of "craving." Gluttony, craving for eternal existence, craving for non-existence... craving comes in many forms, all of them represented by the most common and powerful manifestation, which is sex.

Is there any greater human delight or "bond" (Rahula) than a baby?

Is there any greater human delight or "bond" (Rahula) than a baby?

"There is a legend about the origin of Gautama's harem. At a special event hold on a certain occasion, the young hero Siddhartha was said to have displayed such impressive feats of strength that all the Sakyans [on a frontier province in northwest India that was probably where Afghanistan is now but is traditionally promoted as having been early Nepal, both along the Himalayan foothills] sent a daughter to his household, the total number coming to forty thousand!"

"There is a legend about the origin of Gautama's harem. At a special event hold on a certain occasion, the young hero Siddhartha was said to have displayed such impressive feats of strength that all the Sakyans [on a frontier province in northwest India that was probably where Afghanistan is now but is traditionally promoted as having been early Nepal, both along the Himalayan foothills] sent a daughter to his household, the total number coming to forty thousand!"His father had at least two "wives," sisters, both of whom were the Siddhartha's mother, Queen Pajapati taking over when his biological mother, Queen Maya, passed away a week after he was born.

"Another legend, though it has a misogynist cast... shows another motivation behind Siddhartha's renunciation...the legend tells of his last night in the palace, when, for the first time, he sees the so-called 'real nature of women.' His disgust is so thorough that he decides to leave that very night:

- [His father the king] provided him with the most pleasurable of entertainments... The loveliest of women waited on him... but even music played on instruments like those of the celestial beings failed to delight him. The ardent desire of that noble prince was to leave the palace in search of the bliss of the highest good.... the Akanistha [celestial devas]... suddenly cast the spell of sleep on the young women, leaving them in distorted postures and shocking poses... another, of great natural beauty and poise, was shamelessly exposed in an immodest position, snoring out loud... Another... lay unconscious like a corpse, with her eyes fixed and their whites showing. Another... as if sprawling in intoxication, exposing [herself], her mouth gaping wide and slobbering..."

- ART: Paul Desire Trouillebert's "The Nude Snake Charmer" or La charmeuse de serpents, and John William Godward's "The Tambourine Girl," 1906 (public-domain-images.blogspot.com)

No comments:

Post a Comment