Thoreau the Buddhist

Rick Fields (How the Swans Came to the Lake, Shambhala) Thoreau's Walden experiment had as many aspects as the man who lived it. Certainly one of them was to demonstrate how little one really needed to live well. But his primary purpose was to demonstrate something to himself, to "transact some private business with the fewest obstacles. This "private business" was in the nature of what we would call contemplation. Thoreau was constantly tracking his own nature, which to him was not necessarily other than nature itself. His method was quite simple: More>>

Thoreau's Walden experiment had as many aspects as the man who lived it. Certainly one of them was to demonstrate how little one really needed to live well. But his primary purpose was to demonstrate something to himself, to "transact some private business with the fewest obstacles. This "private business" was in the nature of what we would call contemplation. Thoreau was constantly tracking his own nature, which to him was not necessarily other than nature itself. His method was quite simple: More>>

George Edward Loper

Henry David Thoreau's woods surrounding Walden Pond in 1996 (george.loper.org)

The Woods at Walden Pond

Fed up with business distractions, Thoreau set out to find some peace and quiet to work on his first book, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. Ralph Waldo Emerson (whose constant companion were early translations of Indian spiritual literature) offered him free use of his woodlot along the northern shore of Walden Pond.

While at Walden, Thoreau walked, studied, wrote, traveled about, and even hosted an anti-slavery fair. In 1846, Thoreau stayed in jail overnight for refusing to pay his poll tax as a protest against his state's role in upholding slavery.

In his 1849 essay "Resistance to Civil Government," Thoreau states "I did not for a moment feel confined and the walls seemed a great waste of stone and mortar." Of course, his stay in jail was among the shortest in Middlesex County's history (Carlos Baker, Emerson Among The Eccentrics, p. 269).

In his 1849 essay "Resistance to Civil Government," Thoreau states "I did not for a moment feel confined and the walls seemed a great waste of stone and mortar." Of course, his stay in jail was among the shortest in Middlesex County's history (Carlos Baker, Emerson Among The Eccentrics, p. 269). In his essay "Walden" (The Cambridge Companion To Henry David Thoreau edited by Joel Myerson, Cambridge Univ. Press, p. 99), Richard J. Schneider notes that Thoreau's cabin is the antithesis of the fancy homes admired by many New Englanders. More>>

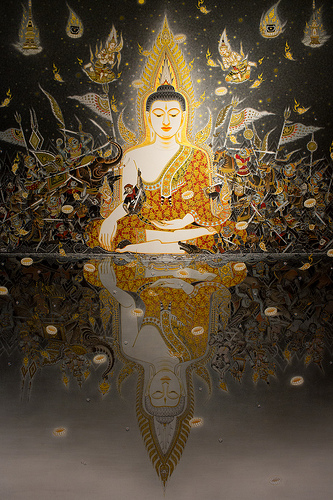

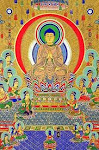

Thoreau said, "Some will chide me for putting my Buddha next to their Christ."

No comments:

Post a Comment